For previous chapters click here

Adventures in the green hell

The Amazon is a place that had always fascinated me as a kid. I imagined a jigsaw-box version of nature, a jungle dripping with exotic animals – jaguars, caimans, snakes and monkeys – where my passions would get lost and consumed. So when BBC producer Huw Cordey offered me a three-month trip to Yasuni National Park, the most biodiverse place on earth, I jumped at the opportunity. I’d never been to any rainforest before, let alone the very finest example. I had no idea back then that it was like being offered a date with a beautiful model, full of excitement and allure, only to get her knickers off and discover she had a cock and balls.

At just 3,800 square miles Yasuni National Park in eastern Ecuador is small, but its location on the meeting point of the equator, the Andes and the Amazon rainforest is what makes it unique. This precise spot on the planet creates an ecosystem so perfect for life that the number of species of birds, amphibians, reptiles, mammals, invertebrates and plants reach their maximum levels there. Up to 100,000 insect species can be found in a single hectare – that’s the same as in the whole of North America. Yasuni boasts 569 species of birds, 500 species of fish, over 4,000 species of plants; I could go but I’d soon run out of ways of rewording the park’s Wikipedia page.

The rainforest I discovered on my first hike with Huw after the four-day journey in was dark and forbidding. The rain was incessant, soaking us through and making the paths exhaustingly slippery. On the occasions I could look up from where my feet were going to slide next, there was no life to see; a green ceiling of dense foliage hid everything. I was bitterly disappointed. Like a pushy father trying to enthuse a reluctant teenager, Huw tried to make excuses for the place; but after my first day in the rainforest I was ready to leave the stinking place. The idea of the three months that lay ahead of me filled me with dread.

My task at Yasuni was to film various animal species and their behaviours – Huw had drawn up an extremely long list – in the forest around a biological research station called Tiputini. He’d detailed sequences of macaws feeding in fruiting fig trees, army ants bivouacking in the buttress roots, woolly monkeys raising their babies in the canopy, tanagers bathing in bromeliads and the exotic dance of the male wire-tailed manakin. Huw was, like most men at the Natural History Unit back then, posh and bullish, with an exhausting Protestant work ethic that demanded absolute commitment at all times. He hadn’t anticipated the 24-year-old pothead layabout that he got to know. Our relationship quickly cemented into that of a disappointed father and his hopeless son. I assumed Huw had given me this big break, shooting sequences on the landmark BBC2 series Andes to Amazon, on the basis of the quality of my previous work; but knowing him as I do now, it was because I was cheap and he could ship me out to buttfuck nowhere in the Amazon, settle me in for a few days and leave me alone for months.

I wouldn’t say I enjoyed my first couple of weeks at Tiputini, but I did eventually settle into a routine of walking trails and becoming familiar with my new home; and with that the forest began to expose itself. Most days I’d wake before sunrise after a sleepless night of sweating, and swatting mosquitos and cockroaches off my back, then I’d head quietly in the pre-dawn gloam along a dark trail through the forest for perhaps twenty minutes to a canopy tower, whose rickety, termite-chewed wooden staircase zigzagged impressively up the side of an enormous kapok tree. The climb up, carrying a full film kit, was exhausting, and I’d be sweating profusely as I ascended the 140 or so steps to reach the broad platform at the top, which was supported by a fatherly hand of giant branches wreathed with orchids, vines and epiphytes. The view was spectacular, the pristine forest extending on all sides as far as the eye could see.

My morning treat would be to sip coffee from my flask and watch the forest awake. It was peaceful and calming. To look down across the unbroken canopy with a pair of binoculars as the sun rose revealed the species the green ceiling below kept hidden – troops of squirrel monkeys feeding and chirping as they bounced between fruit-laden trees, flocks of bright green parrots hanging from the ends of branches as they foraged for nuts and seeds, Couvier’s toucans sitting high on the treetops, incessantly announcing their territories with a haunting call. On mornings when the night mist cloaked the canopy and blocked the sun, only the scarlet and blue-and-gold macaws could be seen, their brilliant rich colours set against a muted palette of greys and greens, squawking loudly to each other as they headed out in pairs high over the forest. Below the canopy all life remained hidden, only hinted at by the operatic melange of birdsong, the incessant backing track of cicadas and the occasional call of a monkey.

To concentrate on a single spot with the binoculars would reveal the extraordinary abundance of birds – paradise flycatchers, oropendolas, tyrant flycatchers, many-banded aracaris, tiny hummingbirds and enormous harpy eagles. Some were brown and drab, like the screaming piha, some utterly extraordinary, like the turquoise and purple spangled cotinga or the paradise tanager, a bird so vividly marked, with its crimson back, electric cerulean breast and face mask of fluorescent green, that it looked fake. I was always excited by the elaborate names of the birds; some were descriptive, some named after their ‘discoverer’ from the Old World, and others after their habits. When I got bored after the sun had risen and quietened all the creatures, I’d sit and make up my own names for the birds, then write letters home to friends and family, regaling them with the extraordinary species I’d seen – white-breasted spitters, deep-throated gobblers and, of course, the impressive spunk-chested cockwarbler.

The idea of sitting in the canopy tower watching the forest below was always much more appealing than the actual experience. There’s no salt in much of the Amazon and so it’s highly prized by all creatures. By mid-morning, when the heat of the day set in, I’d be dripping in sweat, making me irresistible to a whole host of insect species, tiny sweat bees in particular. They didn’t sting, that was the sweat wasps; instead they crept and crawled into my eyes, nose, ears and mouth. They writhed through my sweat-damp hair, tickling and itching my scalp. I tried to be Zen as the first few found me each morning, but as the numbers built to a swarm around my head I’d eventually lose the ability to remain calm and oblivious and would explode in rage, leaping about, swatting my hair and face and attacking the air in a fruitless dance, usually while hacking my guts out to remove the bee that had lodged itself at the back of my throat. These bees released a pheromone when I killed them, attracting more of their kin, until trying to maintain the slightest semblance of tranquillity and detachment on the canopy tower became quite impossible.

I found that first month at Tiputini tough. The humidity of the rainforest made working incredibly uncomfortable, I was exhausted physically and my self-motivation soon took a nose dive. It was hard forcing myself out of bed an hour before dawn every morning, throwing down a quick breakfast and then loading my body up with so much kit that I could barely walk, then trudging alone through the darkness to search for a creature I knew I was probably never going to see, while fighting off mosquitos and biting flies. Everything involved sweating, and the constant damp began to rot my clothes, until I acquired an odour that was both unpleasant and inescapable. My belongings all turned green as mould consumed them.

But as the weeks went by I slowly began to harden to forest living. I remember vividly the moment I didn’t swipe a cockroach off my back while I lay in bed trying to sleep. Instead I just rolled over and resigned myself to spending the night in a bed crawling with roaches, some three or four inches long. I stopped looking for snakes in the bathroom every time I went in; the two boa constrictors that lived in the thatch above the toilet rarely moved, so we became friends. One morning I picked my underpants from the floor to discover two hand-sized phoneutria spiders (aka Brazilian wandering spiders) clinging to the underside of them. One ran up my arm, flooding me with adrenaline as I shrieked and flicked it off in panic, before it scuttled off under my bed. I’d already learned that death from powerful neurotoxins following the bite of a phoneutria could actually be better than the alternative – an agonising, painful erection that lasted up to twenty-four hours, followed by impotence. Indeed, scientists are now looking into the venom of the phoneutria spider to see how it works on the old John Thomas. Let’s hope they wear thick gloves.

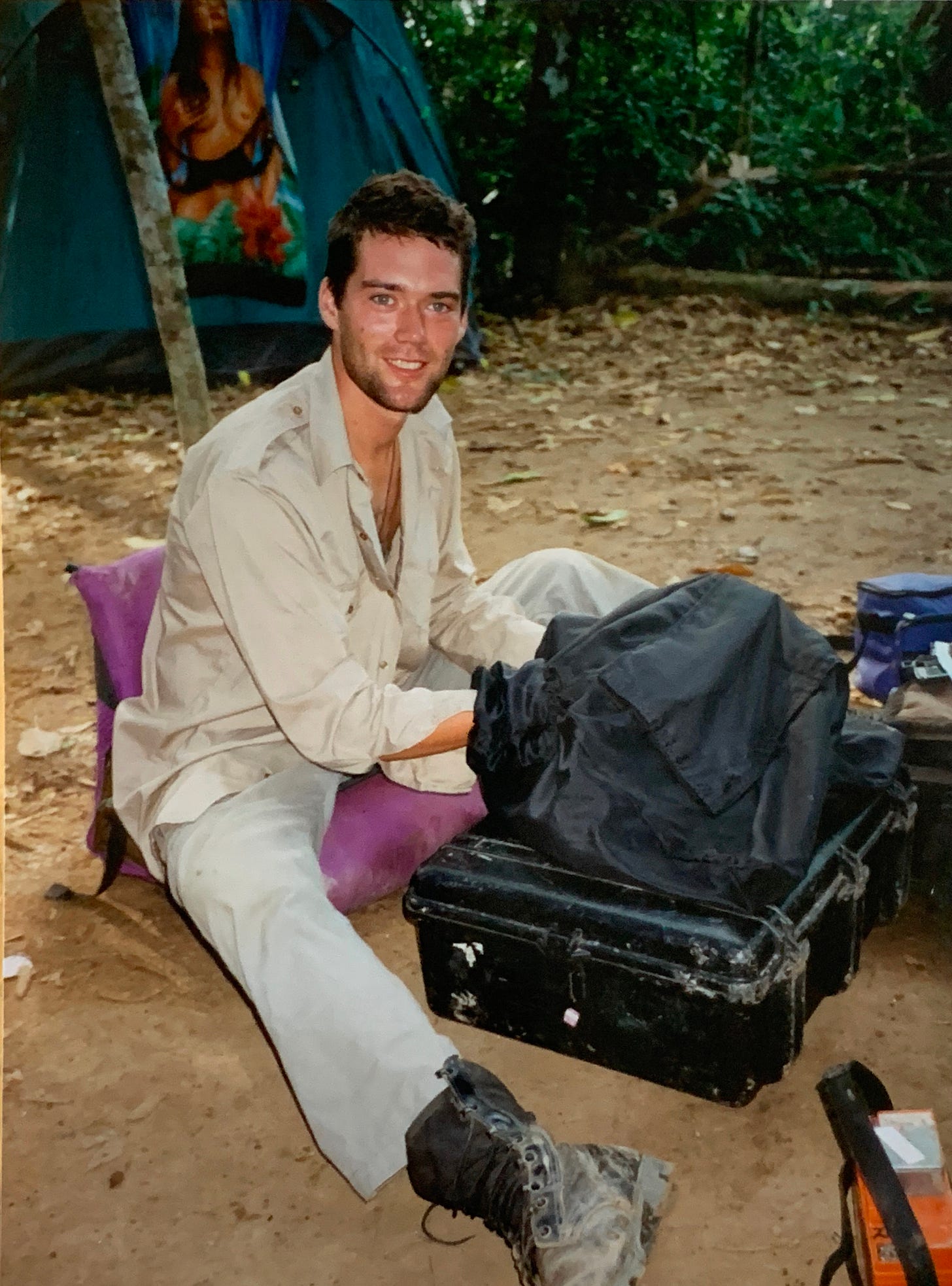

Chris Cole, Huw’s assistant producer, arrived halfway through the shoot and helped dispel my loneliness, appearing on the dock down by the river one afternoon after his long boat trip in. He bore gifts, like a modern and degenerate version of all three wise men: a bottle of Johnnie Walker, a large beach towel emblazoned with a picture of a naked Brazilian woman with huge tits, and a much-needed porno mag. He and I had started out in the business together and were the same age, and it was a real relief to have somebody who not only spoke the same language as me but also shared my sense of humour. Chris picked me back up, readjusted my focus and motivation, and inspired me to take on the more complex sequences detailed on Huw’s list.

There was a spot half an hour from the research station, along the edge of one of the trails cut for students and scientists, where male wire-tailed manakins displayed along branches to attract females. Several males worked the area, known as a lek. The manakins seemed shy when Chris and I approached, so we set up a small scaffold in the understorey and put a hide on it, a few feet from one particular male who favoured a specific branch. When I got in and focused my lens on the little bird, his character began to reveal itself. He was cute and quirky, about the size of a sparrow, with a crimson red head, a bright yellow throat and chest, and a black rump. Two long, thin, curled feathers – the two he got his name from – extended quite dramatically from his otherwise stumpy little tail.

He’d hop between a few branches in rotation and each time he landed he’d perform a little dance, which combined flitting at high speed backwards and forwards, while moving up the branch, then skipping from side to side like a high-speed moonwalk, calling all the while. He was wonderful to watch, like a mini Michael Jackson. His aim, unlike Michael Jackson’s, was to attract an adult female with his elaborate display, and he worked obsessively on his moves. I filmed his dance from every angle and changed lenses for wides, mid-shots and close-ups, until there was nothing left to shoot but the event he and I were actually there for – the arrival of a female. But after a week of sitting in the hide from dawn to dusk, plucking ticks off my balls with pliers and shooing out the enormous blue hornets that kept coming in to fly around my face, not a single female bird had appeared.

Then one afternoon, bored out of my mind, I decided to film yet another identical shot of the manakin skipping along his little branch. As I squinted through my fogged-up viewfinder, trying to keep him in focus, a dull green female suddenly appeared on the branch. He immediately turned away from her, dipped his head and then, in reverse, danced towards her, showing off his arse and calling frantically. As he reached her, she raised her neck slightly, allowing him to repeatedly tickle his long, thin tail feathers under her chin for a few seconds before she suddenly vanished back into the tangle of the forest. His gaze remained fixed awhile on the place where she’d gone, and I could feel his disappointment. His remorse was brief, though, and within a minute he was dancing again. I admired his commitment to getting laid.

I sat back from my viewfinder so relieved and excited. It had taken sitting all day long for more than a week in a tiny canvas box to get that few seconds on film. Tactile stimulation like that in birds had never been filmed before. I loved firsts, and it really lifted my spirits. Luckily I didn’t find out until I returned home months later that my friend Martyn Colbeck had already filmed the mating dance of the wire-tailed manakin for the David Attenborough series The Life of Birds a few years earlier, and done a much better job of it than me.

The more my time in Tiputini became normal life, the more I began to enjoy it. I eventually stopped reacting to mosquito bites, so I could afford to ignore them. My body became accustomed to the humidity and heat and grew physically stronger, which meant carrying the heavy camera equipment around was that much easier. Periods of loneliness were often pinpricked with visits from groups of research students from the US, including girls whom I’d occasionally manage to cop off with.

Many of the world’s top neotropical ecologists would visit Tiputini, which meant I got to hang out with them. We’d discuss their work over dinner and I’d suck up all the information I could. With no degree, nor any academic understanding of nature beyond what I’d seen with my own eyes, I struggled to make sense of much of what they said, but I’d grasp the concepts and some of the pub facts and hang on to them. Then I’d use them when talking to the next scientist or ecologist, and slowly I began to form a more layered and informed understanding of the complex environment in which I was living. Over time I began to realise how incredibly precious it was.

Yasuni sits on top of a major oil reserve, one worth billions of dollars to Ecuador. Back then it had one significant oil refinery in it, the flare of which burned so brightly and permanently that it could be seen on a clear night from Tiputini, a day’s journey away. The oil company that owned it controlled who went in and out of Yasuni, and they were very strict. I experienced this one day when returning from an eventful excursion to get a tooth fixed in Ecuador’s capital Quito, where I’d seen a guy shot and killed in front of me.

Arriving back in Yasuni, I was taken into the refinery in a bus full of oil workers. As we drove in through the security gates we passed a small group of Indigenous Huaorani women and children dressed in filthy T-shirts and shorts. They were staring vacantly through the linked fence that excluded them at the ugly mess beyond – a vast tangle of pipes, steaming flues, Portakabin-style offices and, most ominously, a tall stack that burned a giant and ferocious flame with terrifying intensity. Huge trucks and pick-ups rumbled along bare dirt tracks, and men in hard hats and high-vis gilets loitered around. The sight disturbed me. The contrast in that snapped image from the steamed-up bus window was too real and too dystopian.

I met Carlos, a young American guy who worked as the camp manager for Tiputini, and we drove out of the refinery in his pick-up. As we headed back to Tiputini we were flagged down by an excited man with the corpse of a woolly monkey slung around his shoulders. Carlos pulled up on the side of the road and explained, in slightly excited tones, that the guy was crazy. Melano was maybe in his fifties, short and stocky, with thick black tangled hair. He was dressed in a dirty, blood-stained, white and red football top, with black shorts and bare feet. He clutched an old shotgun and a machete, and shouted at Carlos excitedly and aggressively as he drew down his window.

Not knowing what he was saying, I looked at the monkey that he wore like a shoulder bag. A slit had been cut between the bone and the skin at the end of its tail, which its head had been forced through, turning its tail into a strap. Carlos laughed as Melano ranted at him, then asked me to open my door to let the guy ride with us. Melano slung his monkey and gun in the bed of the truck and climbed in, roughly shoving my bags out of the way and squashing me against the gear stick. He barely acknowledged me, just shot me an angry look.

‘What’s he so upset about?’ I asked.

‘I gave his wife a lift last week and he thinks I fucked her,’ Carlos replied.

‘Did you?’

‘Fuck no. Have you seen her?’

I hadn’t. Melano continued for a while, gesticulating at the windows and roof of the car as he shouted. He was a rough bundle of emotion, almost childlike in his unfiltered expressions of anger. He finally explained to Carlos that if he gave his wife a lift in his car again he’d kill him. Considering Melano had apparently already notched the lives of eight other people on the barrel of his gun, his threat appeared by no means empty. Carlos humoured him, while roughly translating to me, and eventually Melano calmed down, although not before having spat all over me several times and drowned me in his terrible breath. I was amused and terrified by the whole experience in equal proportions.

We dropped Melano off a few miles down the road on a nondescript bend on the track, near where he lived in a hut. As he walked off into the forest, Carlos explained how the Huaorani were starting to change as the oil company cut deeper into the National Park. They’d begun settling along the roads that were metastasising into the forest and hunting with shotguns they’d paid for with money the oil companies had given them. Because the shotguns were so much more effective than their traditional blowpipes and curare-tipped darts, the number of animals they killed was rising. The result was a gradual depletion of fauna across large areas of the park.

Carlos told me about the first missionaries that went in to contact the Huaorani, bearing gifts. They’d been dropped off by helicopters in a forest clearing and were killed by spears shortly after. Others followed in their wake, paid for by the oil companies, to tame the so-called savages. They unfortunately survived. We were now seeing the results of that contact. It was my first real experience of what I later learned was a historic alliance between the drilling industry and the church to placate – or remove – Indigenous people.

Back then I didn’t give a crap about human-rights issues, but this one angered me as it was patently unjust and evil. I suspect that such alliances are generally guided by bent morality and justified as necessary progress. But who knows the number of Huaorani that died contracting influenza and other pathogens lethal to isolated people, as a result of their contact with the outside world. I suspect it’s in the hundreds, with entire communities and families destroyed. A terrible history could have been written, if only the Huaorani were literate. But history is rarely written by the losers. Still, we all got cheap fuel and they had their souls rescued by Christ. And let’s not forget ‘they were only a bunch of little brown peasants anyway, so fuck em’ – Luke 29:11.

Army ants in the next instalment...

It sounds primitive Charlie. What were you surviving on?